10. Altruism

PSYG2504 Social Psychology

10.1. Definitions

Prosocial Behavior: Any act performed with the goal of benefiting another person.

Altruism: The desire to help another person even if it involves a cost to the helper.

10.3 Why do we help?

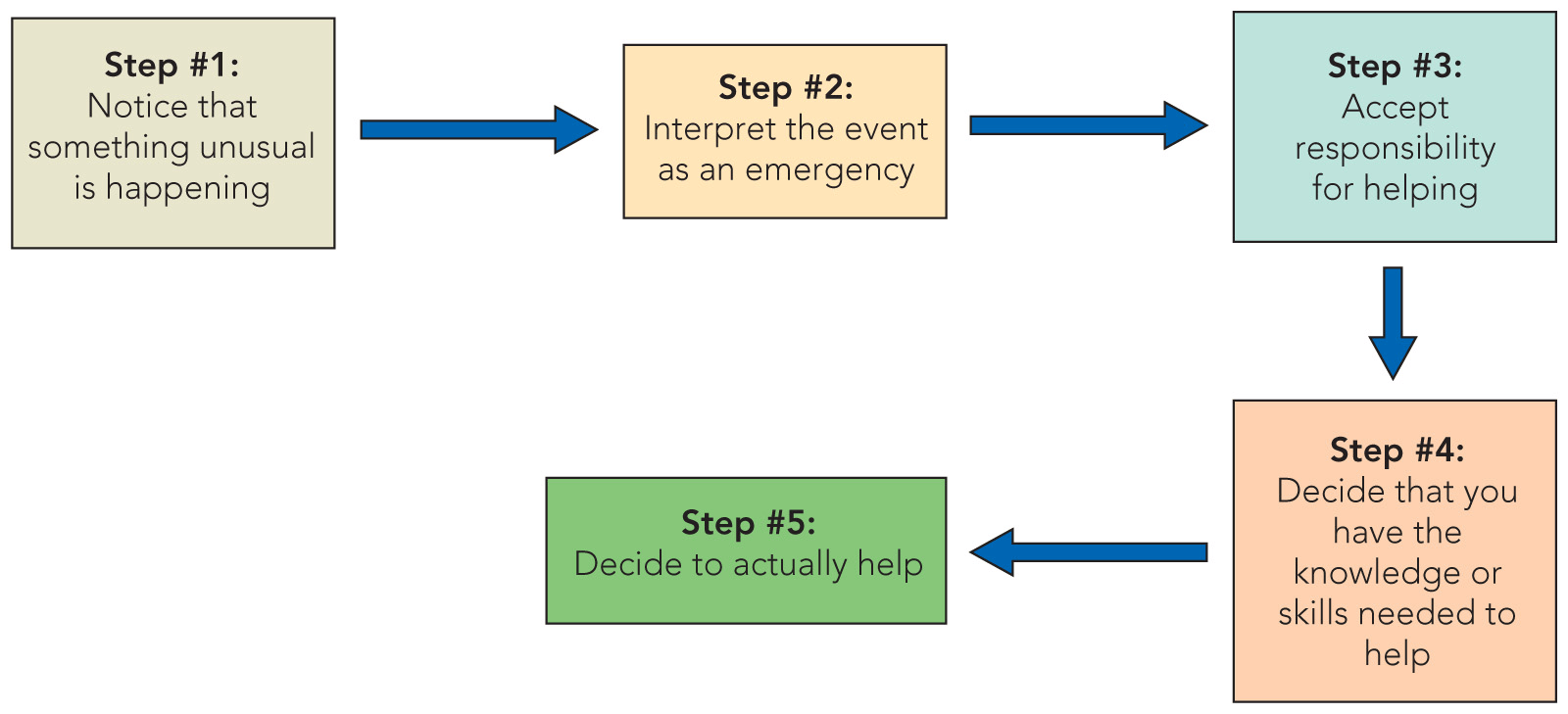

10.3.1 A decision-making perspective (Latané & Darley, 1970)

People decide whether or not to offer assistance based on a variety of perceptions and evaluations. Help is offered only if a person answers “yes” at each step.

Notice the event

When we are distracted or in a hurry, we don’t help.

Correctly interpreting an event as an emergency

Cues that lead us to perceive an event as an emergency (Shotland & Huston, 1979).

- Event is sudden & unexpected

- Clear threat of harm to a victim

- Harm will increase unless someone intervenes

- Victim needs outside assistance

- Effective intervention is possible

Clark and Word (1972) Heard maintenance man fell off a ladder and cried out. Alternative condition: without verbal cues that the victim was injured Help was offered only about 30% of the time.

Deciding that it is your responsibility to help

Being given responsibility increases helping.

Moriarity (1975) Radio at the beach Control: 20% Experimental: 95%

Deciding that you have the knowledge or skills to act

In emergencies, decisions are made under high stress and sometimes even personal danger. Well-intentioned helpers may not be able to give assistance or may mistakenly do the wrong thing.

Crammer et al. (1988) When there is an accident and possible: injury, a registered nurse is more likely to help than non-medical people.

Weighing the Costs and Benefits

At least in some situations, people weigh the costs and benefits of helping People sometimes consider the consequences of NOT helping. However, in other cases, helping may be impulsive and determined by basic emotions and values rather than by expected profits.

10.3.2 A sociocultural perspective

Human societies have gradually evolved beliefs or social norms that promote the welfare of the group.

- Norm of Social Responsibility

Help those who depend on us. e.g. parents, teachers, doctors. - Norm of Reciprocity

Help those who help us (Gouldner, 1960). - Norm of Social Justice

Maintain equitable distribution of rewards.

10.3.3 A learning perspective

We learn to be helpful through reinforcement.

Children help and share more when they are reinforced for their helpful behavior.

Fischer (1963) 4-year-olds more likely to share marbles with another child when they were rewarded with bubble gum for their generosity. (Dispositional praise) ‘You are a very nice and helpful person’ vs. (Global praise)‘That was a nice and helpful thing to do’. Dispositional praise appears to be more effective than global praise.

We learn to be helpful through observation.

Children and adults exposed to helpful models are more helpful. For children, helping may depend largely on reinforcement and modeling to shape behavior, but as they get older, helping may be internalized as a value, independent of external incentives.

10.3.4 Attribution

We are more likely to be empathetic and to perceive someone as deserving help if we believe that the cause of the problem is outside the person’s control.

Myer & Mulherin (1980) College students would be more willing to lend rent money to an acquaintance if the need arose due to illness rather than laziness.

10.4 Who helps?

10.4.1 Mood and Helping

People are more willing to help when they are in a good mood.

- Money: found coins in a pay-phone (Isen & Simmonds, 1978)

- Gift: been given a free cookie at the college library (Isen & Levin, 1972)

- Music: have listened to soothing music (Fried & Berkowitz, 1979)

- Odor: smelled cookies or coffee (Baron, 1997)

Mood-maintenance hypothesis

“Doing good” enables us to continue to feel good.

-

Good moods increase positive thought

-

Limitation of the effect of good mood “Feel good” effect is short-lived

Only 20 minutes in one study (Isen, Clark, & Schwartz, 1976)

Negative moods sometimes lead to more helping

Negative-state relief model suggests that people may help as a way to make themselves feel better (Cialdini, Darby, & Vincent, 1973). Helping made college students feel more cheerful and feel better about themselves (Williamson & Clark, 1989). When people feel guilty, they are more willing to help (Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton, 1994). Helping others may reduce their guilty feelings.

More valid for adults* (e.g. Aderman & Berkowitz, 1970) and less valid for children* (e.g. Isen et al., 1973). Less likely to occur if a person is focused on themselves and their own needs e.g. during profound grief (e.g. Aderman & Berkowitz, 1983).

10.4.2 Empathy

Empathy refers to feelings of sympathy and caring for others.

The emotional reactions that are focused on or oriented toward other people and include feelings of compassion, sympathy and concern. Occurs when we focus on the needs and the emotions of the victim. Fosters altruistic helping.

10.4.3 Personality Characteristics

There is no single type of “helpful person”. The effect of personality on altruism

- Individual differences in helpfulness persist over time

- People high in positive emotionality, empathy, and self-efficacy are most likely to be helpful

- Influences how people react to particular situations, i.e. people who are more sympathetic to the victim in emergency situations respond faster

10.5 Whom do we help?

10.5.1 Gender

- Men are more likely to provide help to women in distress (e.g. Latané & Dabbs, 1975), especially when there is an audience.

-

Men offered more help to women while women are equally helpful to both sexes (Eagly & Crowley, 1986).

-

Women are more likely to offer personal favors for friends and to provide advice on personal problems (Eagly & Crowley, 1986).

- Women provide more social support to others (Shumaker & Hill, 1991). However, men more readily help attractive than unattractive women (e.g Mims et al., 1975).

Motivation may be romantic or sexual.

Przybyla (1985) Undergraduate men watched video Experimental: erotic/Control: nonsexual Situation: a female research assistant “accidentally” knocked over a stack of papers Experimental group more helpful than control 6 minutes compared with control with male (30 seconds) Female participants No difference between experimental and control No difference between male or female research assistant

10.5.2 Physically attractive

Benson, Karabenick, and Lerner (1976). Subjects found a completed and ready-to-mail application to graduate school in a telephone booth at the airport Sample: 442 males and 162 females IV: photo attached belongs to an attractive or unattractive male/female DV: will they mail it for him/her? Results? Attractive: 47% Unattractive: 35%

10.5.3 Similarity

Emswiller, Deaux, and Willits (1971) Confederates dressed as a ‘hippie’ or ‘conservative’ Approached both ‘hippie’ and ‘conservative’ students to borrow a dime for phone call Results Fewer than half the students did the favor for those dressed differently from themselves Two-thirds helped those dressed similarly

10.6 When do we help?

10.6.1 Bystander effect

The presence of other people makes it less likely that anyone will help a stranger in distress.

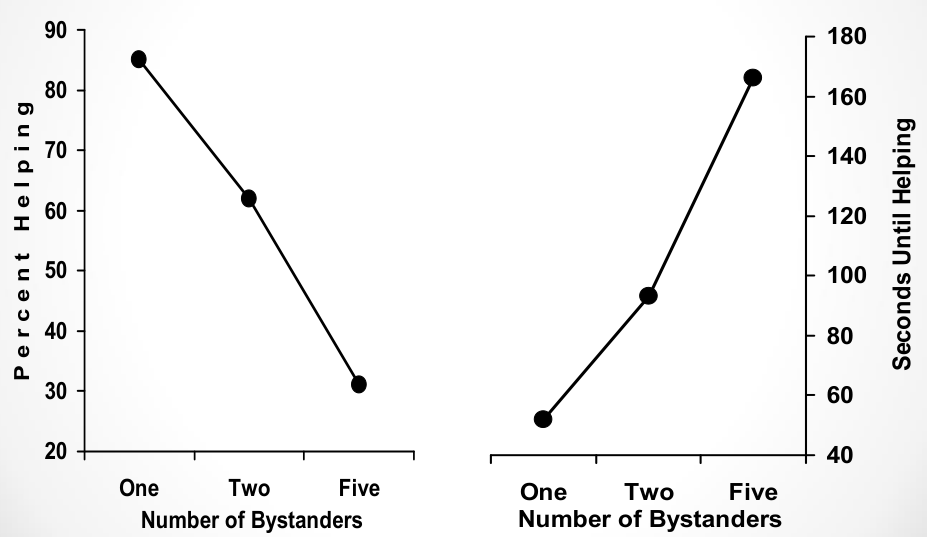

Kitty Genovese murder sparked research of Darley and Latané (1968) Male students in a study of “campus life” Sat alone and talked to another student through intercom Emergency: this fellow student said he sometimes had seizures and he soon began to choke, had difficulty speaking, and said he was going to die and needed help. Then, no more sound

Darley and Latané (1968) IV: number of bystanders: 1, 2, 5 Some students believed that they were the only person aware of the emergency In fact, he heard a recording and there was no bystander Only the way to help was to leave the lab and sought for that fellow student DV1: % of students left and helped DV2: time they waited before acting

Why does the bystander effect occur?

-

Diffusion of responsibility ** The presence of other people makes each individual feel less personally responsible. If only bystander, bear the guilt or blame for nonintervention Assume the others ‘will do it’.

-

Pluralistic ignorance ** Bystanders’ false assumption that nothing is wrong in an emergency because of others.

-

Evaluation apprehension

Concern about how others are evaluating us We try not to appear silly/cowardly in reacting to ambiguous situation (e.g. smoke filled room)

Latané and Darley (1968) pumped smoke into a research room where participants were doing questionnaire IV: alone in the room or with 2 confederates DV: the duration of leaving the room and reporting Result Alone: 1st minute: about 35% stopped and went out to report; 6th minute: 75% Group: 1st minute: 10%; 6th minute: 38% The behavior of other bystanders can influence how we define the situation and react to it

10.6.2 Environmental Conditions

People are more helpful to strangers when it’s pleasantly warm and sunny (Ahmed, 1979).

People are more likely to help strangers in small towns & cities than in big cities (Levine et al., 1994).

What matters is current environmental setting, not the size of the hometown in which the person grew up.

10.6.3 Time pressure

Darley & Batson, 1973 Participants were students studying religion and were asked to give a short talk IV1: Some were told to hurry, others to take their time IV2: assigned topic was either the Bible story or future job opportunities Results IV1: 63% of those not in a hurry vs. 10% in a hurry helped a coughing and groaning stranger they passed IV2: no difference Time pressure particularly caused students to overlook the needs of the victim.