4. Attitudes

PSYG2504 Social Psychology

Our evaluations of any aspects of the social world (including people, objects and ideas).

Feelings, often influenced by our beliefs, that predispose us to respond favorably or unfavorably to objects, people, and events

4.1 Attitudes

Three components of attitude:

4.1.1 Affectively Based Attitude

An attitude based more on people’s feelings and values.

Regarding the positive and negative feelings regarding the stimulus.

People vote more with their hearts than their minds.

We feel strongly attracted to something (or a person), despite the negative belief about him/her (e.g. knowing that the person is a “bad influence”).

4.1.2 Behaviorally Based Attitude

An attitude based on observations of how one behaves toward an object. Based on observations of how one behaviors toward an object.

Do you like Apple products? If you use many Apple products, you may think you really like this brand.

4.1.3 Cognitively Based Attitude

An attitude based on people’s beliefs about the properties of an attitude object.

Implicit attitudes are rooted in people’s childhood experiences, while explicit attitudes are formed in recent experiences (Rudman, Phelan & Heppen, 2007).

- Explicit attitudes

Consciously endorse and easily to report E.g. I dislike people who are always late - Implicit attitudes

Exist outside of conscious awareness Test by Implicit Association Test (IAT)

4.1.4 Attitudes influence Cognitions

IAT: a test that measures the speed with which people can pair a target face (e.g. Black/White, old/young; Asian/White) with positive or negative stimuli (e.g. the words honest or evil) reflecting unconscious (implicit) prejudices.

People respond more quickly when white faces are paired with positive words and vice versa.

https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/education.html

4.2 Attitudes formation

4.2.1 Social learning

The process that we acquire new information, forms of behavior, or attitudes from other people. i.e. by interacting with others, or observing others’ behaviors (imitation)

Social learning occurs in three processes:

- Classical conditioning (learning based on association)

- Instrumental/operant conditioning (rewards)

- Observational learning

4.2.2 Classical conditioning

A basic form of learning in which one stimulus, initially neutral, acquires the capacity to evoke reactions through repeated pairing with another stimulus.

4.2.3 Instrumental/operant conditioning

A form of learning whereby a behavior followed by a positive response is more likely to be repeated.

E.g. Insko (1965) showed that participants’ responses to an attitude survey were influenced by positive feedback on the responses they gave a week earlier.

Reinforcing one’s attitudes with positive feedback means that the attitudes are more likely to survive and be expressed on other occasions.

4.2.4 Observational learning

A basic form of learning in which individuals acquire new forms of behavior as a result of observing others.

4.3 Attitudes predict deliberative behavior

4.3.1 Theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991)

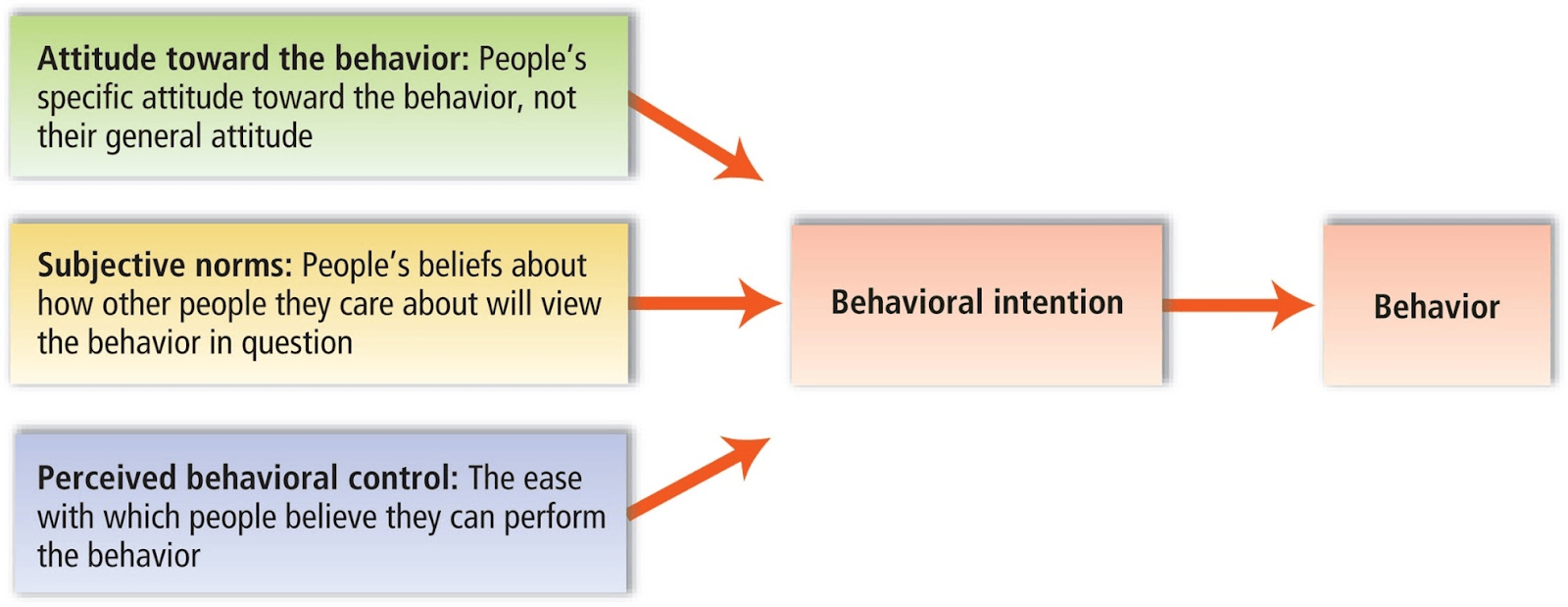

Several factors, including subjective norms, attitudes towards the behavior and perceived behavioral control, determine behavioral intentions concerning the behavior, and, in turn, intentions strongly determine whether the behavior is performed.

4.4 Why does action/behaviour affect our attitude?

4.4.1 Cognitive dissonance

The discomfort that is caused when two cognitions conflict, or when our behavior conflicts with our attitudes.

Dissonance is most painful, and we are most motivated to reduce it, when one of the dissonant cognitions challenge our self-esteem (Aronson, 1969)

Three ways to reduce dissonance:

- Changing our behavior to make it consistent with the cognition/attitude.

- Attempting to justify our behavior through changing one of the dissonant cognition/attitude.

- Attempting to justify our behavior by adding new cognitions.

Less-leads-to-more effect

Less reasons or rewards for an action often leads to greater attitude change.

Festinger and Carlsmith’s (1959) experiment:

Performing a dull task for an hour: turning wooden knobs.

Effect of preconceptions on performance.

Manipulation: $1, $20 or no lie.

Results?

Insufficient Justification

The less incentive one has for performing a counter-attitudinal behavior, the more dissonance is experienced.

Needs to reduce the dissonance internally Vs Overjustification effect.

The effect of promising a reward for doing what one already likes to do

the person may now see the reward, rather than intrinsic interest, as the motivation for performing the task.

Children promised a reward for playing an interesting puzzle or toy

Four conditions to produce dissonance:

- The person has to realize that the inconsistency has negative consequences – e.g. the smokers realize smoking causes ill health

- The person has to take responsibility for the action – e.g. smokers are freely responsible for the decision to smoke

- The person has to experience physiological arousal – e.g. smoking causes anxiety as it could cause ill health

- The person has to attribute the feeling of physiological arousal to the action itself - e.g. smokers need to be able to link the feeling and the behaviour

Alternative strategies to resolve/reduce dissonance

- Change the behaviour to more consistent with our attitude.

E.g. smoking fathers quit smoking. - Acquiring new information to support our behaviour.

E.g. finding evidence that smoking away from the children would do no harm. - Deciding that the dissonance is not important.

Smoking in the presence of children is not important.

Indirect methods to reduce dissonance

To restore positive self-evaluations:

Self-affirmation – restoring positive self-evaluations that are threatened by the dissonance.

E.g. Smoking father does not focus on his smoking behavior; but a responsible father as he earns the living.

Dissonance can be a tool for beneficial changes in behavior

Hypocrisy induction – The arousal of dissonance by having individuals make statements that run counter to their behaviors and then reminding them of the inconsistency between what they advocated and their behavior.

The purpose is to lead individuals to more responsible behavior.

Aronson, Fried, & Stone (1991); Stone et al. (1994)

Asking college students to compose a speech describing the dangers of AIDS, advocating the use of condoms (safe sex)

Group 1: students merely composed the arguments

Group 2: after composing the arguments, the students were to recite them in front of a video camera and were told that the audience were high school students

Highest dissonance: Group 2

4.4.2 Self-perception theory (Bem, 1972)

When we are unsure of our attitudes, we infer our attitudes from our behavior and the circumstances in which this behavior occurs. e.g. You choose to eat oranges from a basket of seven kinds of fruit and somebody asks you how you feel about oranges.

For 10 years the Cognitive dissonance theory was the only theoretical interpretation of effects of behaviors on attitude change.

Self-perception theory and cognitive dissonance theory make similar predictions but for different reasons.

Same prediction on Festinger and Carlsmith’s (1957) experiment.

Why the actions affect the attitudes?

- Cognitive dissonance theory – we justify our behavior to reduce the internal discomfort

- Self-perception theory – we observe the behavior and make reasonable inferences about our attitude

Both theories may be correct:

- Self-perception theory seems more applicable when people are unfamiliar with the issues or the issues are vague, minor, or uninvolving

- Cognitive dissonance theory seems more applicable to explaining people’s behavior concerning controversial, engaging, and enduring issues